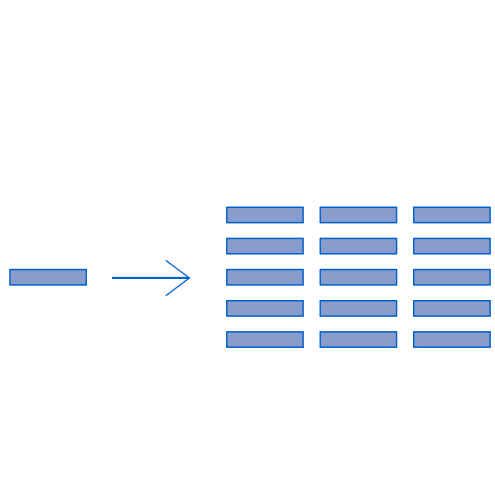

Frida Escobedo understands architecture as a means of asking questions—questions directed at oneself, at a place, and at society. Her work is based on a fundamental principle visible in many of her projects: working with modules and grids that condense into complex shells, façades, and spatial layers. These modular systems are not merely tools of design but an expression of thinking in fragments, transitions, and relationships. Through the repetition of small elements, their deliberate variation, and their combination, Escobedo’s architecture creates spaces and designs that do not appear monumental, but instead stand out through a quiet complexity.

A particularly striking example of this principle is the Aesop Store in Brooklyn. For the design of the store, Escobedo had more than a ton of Oaxacan soil imported from Mexico and turned into bricks, which form the walls in a staggered, rhythmically set pattern. The tactile wall surface simultaneously tells the story and journey of the material, making the cultural overlap tangible without aggressively spelling it out. Here, the grid serves not only as an ordering principle but as a carrier of meaning. The simple building block becomes a “modular thing that can generate enormous aesthetic complexity.”

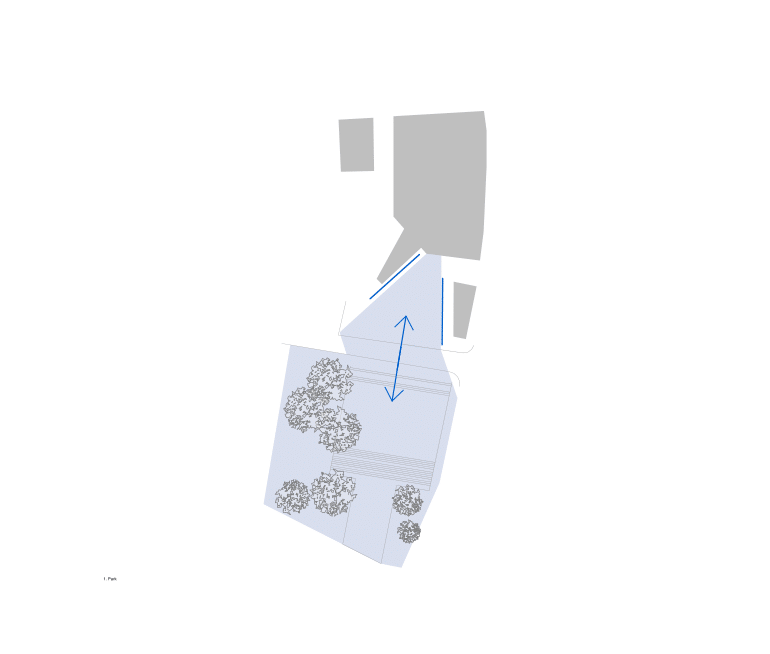

The same principle is evident in the 2018 Serpentine Pavilion. Escobedo designed an open courtyard space enclosed by a wall of English roofing tiles, reinterpreted as celosías—a traditional Mexican element used for ventilation and shading. These walls, made up of small, serial elements, create a play of light and shadow, openness and boundary. They enclose the space while simultaneously redefining it through their permeability. Movements of the sun and shifting perspectives continuously transform the space without altering the structure itself. Such subtle observations point to the temporality of architecture, a theme of particular importance to Escobedo.

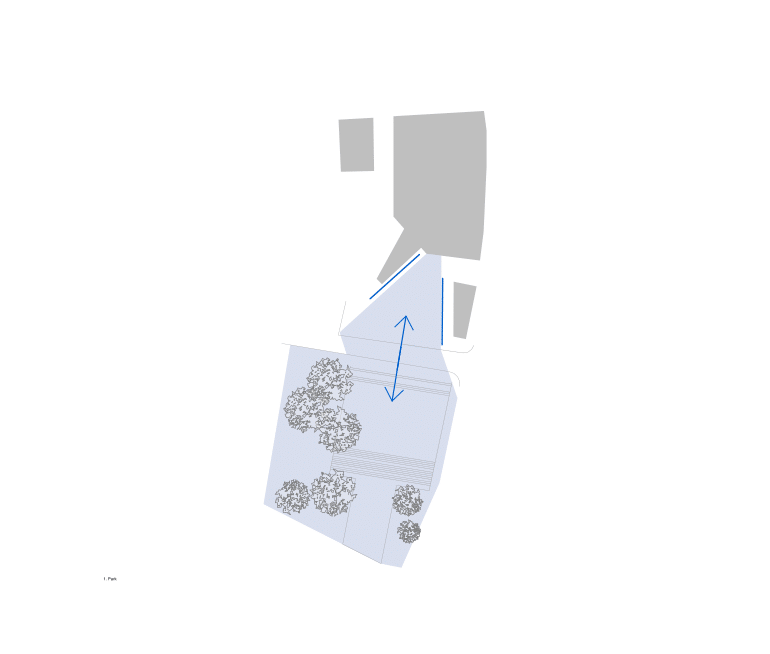

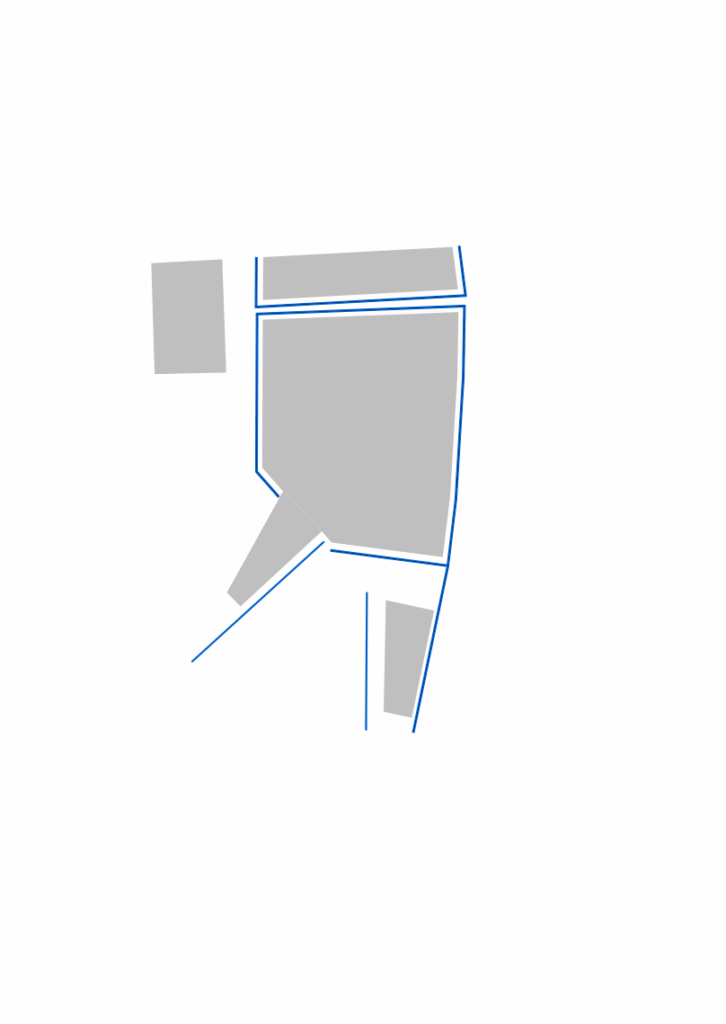

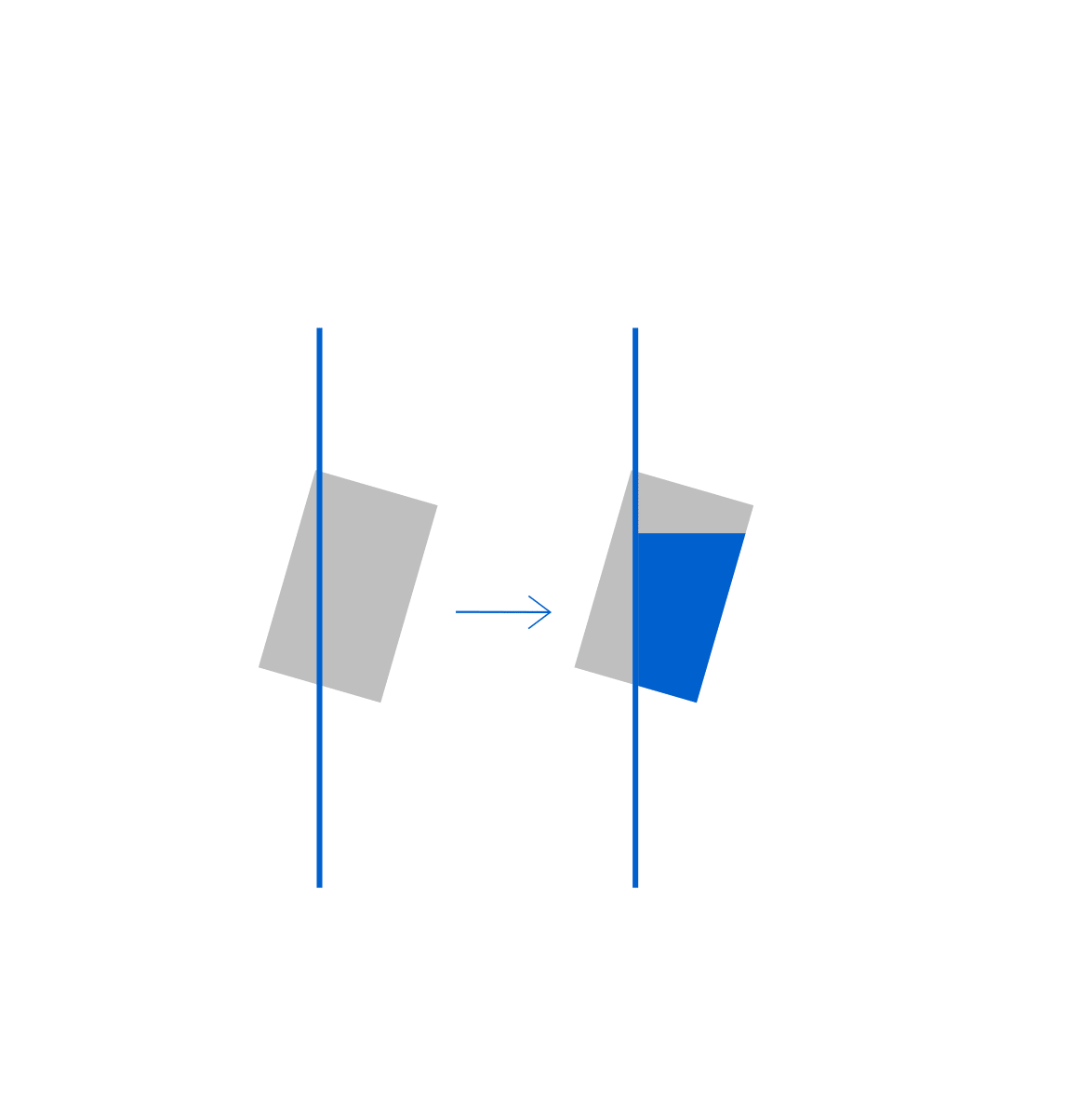

The pavilion also reveals her sensitivity to context: its outer walls align with the Serpentine Gallery, while its interior layout overlaps with a second, implied rectangle based on the Prime Meridian—ensuring that the pavilion retains its meaning even if relocated. Escobedo’s works adapt to their context without dissolving into it.

Her modular systems are closely tied to another of her central design principles: working with fragments and thinking in layers. Escobedo’s understanding of architecture as a sequence of snapshots, overlays, and traces goes back to the seminar The Ruin Aesthetic with Erika Naginski, which she attended during her time at Harvard. From her perspective, every building is a “ruin of the original idea”—a statement that consciously abandons the notion of completion. A building is never truly finished but changes continuously with its use, its context, and time itself. Architecture, therefore, is not static but adaptable.

Beyond form, Escobedo’s grids also serve as tools for social reflection. In her publication Domestic Orbits, she examines the division of domestic spaces in households where servants and families live under one roof, highlighting how hierarchies are also reflected in architecture. Her work seeks not only to expose such structures but to make them permeable. Walls, for Escobedo, are not simply boundaries but frameworks, design elements, and filters between inside and outside—opportunities to make social relations visible and open to change. Inside and outside are often not strictly separated but exist in relationship, capable of interaction.

This approach is closely linked to her deliberate choice of materials: natural, raw, and often locally rooted building materials that age well and develop a patina over time without requiring maintenance. The use of simple, affordable materials such as concrete, brick, wood, or earth underscores her principle of the “modest gesture.” It is not about spectacle but about a quiet presence that grows over the years. Respecting budgets—especially in early projects—is itself a design theme. Her collaboration with photographer Rafael Gamo illustrates this approach: rather than producing perfect images, they aim to document change, transformation, and life within buildings.

Her stance is shaped by a calm persistence. She avoids grand statements but works consistently and with deep curiosity. The goal is not control over a building but to open it for appropriation and change. For Escobedo, architecture is a means of approaching the world—not of staging herself. Her work does not aim to deliver finished statements but to raise and explore questions. Examples include the Civic Stage and the El Eco Pavilion, where it is ultimately the visitors who shape and define the space.

That many of her projects involve renovations, additions, and transformations of existing buildings is no coincidence. Escobedo first approaches a place as an observer, then adds new layers without erasing the old. In Mexico City, where her studio is based, this layering of old and new is omnipresent. Her buildings emerge like sediments: stratified, legible, open.

In Mexico, there is a highly practical approach to architecture. Young architects are given opportunities early on to work on a wide range of projects, thanks to a hands-on culture. Within the new generation of Mexican architects and related fields, interdisciplinary collaboration is increasingly common. Escobedo often gravitates toward projects that blur the boundaries between art and architecture.

Escobedo’s architecture is not loud or monumental—it demands attention. It engages with political, social, and aesthetic questions, not through overt theses but through carefully placed gestures. Her modules, fragments, and grids generate spaces that are as complex as they are accessible. Her work balances restraint with expressive power, showing how much can be said with little. The designs do not impress through scale but through depth. They invite us to look closer.